Coins

DATAMES

Stater

Mint: Tarsus.

Date: c. 370s – before Datames’ death in 362 or 361 anyway.

Legends: 𐡁𐡏𐡋𐡕𐡓𐡆 {B’ltrz} / 𐡕𐡓𐡊𐡌𐡅 {Trdmw} (Baaltars / Tadanmu). Datames was known in Persian as Datama, which via some morphological mutations was rendered in Aramaic as Tadanmu or, more curiously, Tarkamuwa.

Description: Just an extremely attractive coin. The obverse is a little conventional, but the reverse figure –intended, no doubt, to be Datames himself– is a work of very particular distinction. His Persian nobleman’s outfit is carefully rendered – note the outer jacket with hanging sleeves and the distinctive satrapal headgear. But the posture is the most particular delight. We catch our issuer in a moment of stern contemplation, perfectly captures by the engraver. He sits, downcast, the face preserved well enough to detect a melancholic note, testing the balance of an arrow. This pose would, in the eras of the Seleucidans and Parthians, become exhaustingly familiar, but here it is striking and new and curious. It contrasts strikingly with the standard depiction of the Persian monarch, against whom Datames struggled at length and unsuccessfully. The Great King had to be a warrior – to justify his rule to his barons and subjects he was obliged to seem active and courageous. And, thus, on his coins he rushes forward, a weapon in each hand. No such posturing for Datames – instead he presents himself as calm and contemplative, his weapon sitting quietly beside him. To launch a revolt against the King of Kings was as explosive and decisive a decision as could be made, and, perhaps, here we catch Datames giving the matter the deep consideration required. There’s an intriguing psychological density to it, regardless of how much of it was actually intentional. The winged sun-disk, properly the fravashi, carries surprisingly complex (and contradictory) meanings – in general terms, and to no doubt lose the results of a subtler interpretation, it suggests divine approval and protection of Datames.

There’s less to say about Baaltars – he sits with his various cultic items and the entire scene is surrounded by a charmingly naïve city wall. Baaltars was, of course, the tutelary god of Tarsus, which strongly suggests these coins were minted there. The location of Datames’ actual satrapy is a slightly obscure matter – Nepos gives him “Cilicia next to Cappadocia”, but Diodorus gives him Cappadocia itself. The problem is probably insoluble – at any rate, if he wasn’t governing Cilicia as satrap, no doubt he promptly secured it for himself after having revolted. His father had certainly once been satrap there, so we might imagine he had local supporters to draw on.

I should treat briefly on the legs seen here – both figures have (vis-à-vis the Alexandrine taxonomy) “straight legs” and, while Datames is posed naturally, Baal’s torso is twisted towards the camera highly unnaturally. This seems to have been the standard way to depict seated deities in this part of the world – the most familiar rendering is the Baal seen on the staters of Mazaeus. There’s a highly intriguing “low chronology” of Alexander’s coinage, which posits that he struck in the name of his dead father until he reached Cilicia and encountered the emissions of Mazaeus – after which he began to mint in his own name and types, with a Zeus modelled on the customary straight-legged Baal for the comfort and convenience of his new subjects. The evidence, if I recall, inclines against this theory, but it’s curious to consider the resemblance.

CHERSONESOS

Æ20

Mint: Chersonesos. “Cher” under the hoplite on the reverse.

Date: 350-300 BC, per auction descriptions, which are all I have to go on. I possess none of the standard resources for these.

Legends: [none] / XEP

Description: I must guiltily admit I know very little about these. The only colour I can find comes from a CNG listing which suggests the types refer to a recent victory of Chersonesos over Olbia, their not particularly close neighbours. I pass this on without comment. The crouching hoplite type is enormously reminiscent of a coinage of Kisthene in Mysia, which is dated to the 350s. This earlier dating, plus the general improbability of a city closer to the Greek mainstream copying its types from an obscure colony in Ukraine, suggests Kisthene is the prototype and Chersonesos the imitator. The chariot type is more elusive: it suggests (in overall feeling, if not so much in detail) the reverse of Philip II’s staters, which no doubt got around the Black Sea in quantity. If this was the source, it would probably push the date of these coins somewhere closer to the middle of the 350-300 range.

KYME

Tetradrachm

Mint: Kyme (see the map below). The one-handled cup on the reverse is distinctive to coins of this city.

Date: The authorities decline to date the various Heracles tetradrachms with much exactness – a couple are put, tentatively, at the end of Antiochus I’s reign, the rest sometime in Antiochus II’s. More follows below on the dating. Legends: ΒΑΣΙΛΕΩΣ ΑΝΤΙΟΧΟΥ (of King Antiochus). Various monograms around.

Description: This coin is the product of a poorly-recorded and evidently turbulent episode in Seleucid history – the ambitious Eumenes I of Pergamon, taking advantage of, in turn, the weakness of Antiochus I and the confusion following his death, went on the offensive in Ionia and Aeolis and brought much of the Seleucidan territory there under his control. In response to this Pergamene aggression –so it is hypothesised– several Aeolian cities, having resolved to stay loyal to the house of Seleucus, banded together in an anti-Attalid league of some description. In that context, these coins begin to appear. Tetradrachms with the portrait of Antiochus I and a seated Heracles on the reverse were minted by Aegae, Kyme, Myrina and Phocaea – a glance at the map below shoes the cities nearby to each other and, equally pertinently, dangerously close to the capital of the rapacious Pergamenes.

The dating of these coins is, as noted, fairly obscure. A handful (emitted by Kyme and Phocaea) are attributed to the very end of Antiochus I’s reign, the rest later. Beyond that it seems nothing can be confidently said – none of these cities minted for Seleucus II, suggesting that they fell to the Attalids before 241. The basic système for the Kyme coinage is that the series is thought to have begun with relatively characterised portraits, which descended into increasing idealisation and abstraction. Mine would fall around the early-middle of the series, by that criterion – so, somewhere in the reign of Antiochus II. Good and less good work seems to be found on the reverses from start to finish.

The reverse type is, of course, a highly unusual departure from the typical Seleucidan Apollo, although we see some resemblance in the seated posture and arrangement of the legs. Why these cities, ostentatiously minting in support for the Seleucids, simultaneously discarded their characteristic reverse, is the vital, but unanswerable, question. The depiction of Heracles resting after his successful labours suggests –very vaguely– the commemoration of some successful military exploit. Perhaps the improvised resources of the cities were able to defeat some initial Pergamene encroachment, and this success gave the impetus for the foundation of their league in the first place. That the cities felt a victory of such fundamental importance ought to be commemorated on their new coinage is a natural supposition – though this is all a guess. The boldness shown in departing from the standard Seleucidan reverse certainly suggests the league was confident its own resources – despite having declared for Antiochus, the cities, no doubt conscious of their antique dignity as pre-Hellenistic foundations, perhaps wished to remain at some distance from him following the expected defeat of Pergamon. Curiously, a final issue of Aegae reverts to the usual Apollo type – a final desperate appeal to Seleucid authority before the city’s fall to the Attalids, Newell conjectures. The Heracles coins were once thought to have all been issues of Antiochus Hierax, but this is no longer credited.

To digress briefly on the existence of this supposed Aeolian league – the only evidence we have for it is the coins themselves. This is strong enough, a far as it goes – four cities, none of which had at the time been minting, suddenly begin to emit coinage with a linked, and peculiar, reverse. We also see a similar ΦΩ monogram (as on this coin here) on the reverses of coins from Kyme, Myrina and Phocaea, perhaps the mark of a league official who superintended all the mints together. More guesswork.

Finally, to conjecture wildly, one might wonder whether this reverse inspired the seated Heracles reverse of Euthydemus I a few decades later. Euthydemus, we read in Polybius, was “a native of Magnesia”. This is generally taken to be Magnesia on the Maeander. We may note, however, that Magnesia ad Sipylum lay very close to the cities which issued the Heracles coins.

GALBA

Denarius

Mint: Rome.

Date: c. later 68. The dating of these is vague and not worth exploring here.

Legends: IMP. SER. GALBA CAESAR AVG. / DIVA AVGVSTA (Imperator Sergius Galba Caesar Augustus / The Divine Augusta (i.e., Livia)

Description: A superbly cadaverous portrait of S. Sulpicius Galba. The expression reads to me as something between contempt and pity – we may imagine this ghost of the antique republican virtues risen from his grave, casting a mournful eye on the follies and vices of the Neronian era. Galba, of course, turned out to be less of a vengeful spirit and more of a living corpse – his skeletal appearance invited mockery and he proved too decrepit to overcome the younger, less scrupulous, more attractive Otho. Having arrived in Rome, we read in Tacitus, Galba “aroused ridicule and scorn among those who were accustomed to Nero's youth, and who, after the fashion of the vulgar, compared emperors by the beauty of their persons.” Those who missed Nero looked favourably on his stylish companion, and “the gossip of those who compared Galba's old age and Otho's youth” was rife. Galba was, we read, completely bald, and so his coiffure here is a little improbable. The emperor, as commander-in-chief, was obliged to be a virile man – and perhaps the mores of post-Neronian Rome obliged him to be an attractive one as well.

On the reverse we have the deified Livia, a familiar figure from the exhausting denarii of Tiberius. Here, for some variety, she stands up. Livia, for reasons now lost to us, had assisted Galba in in the earlier part of his career, to the point of obtaining him a consulship, and had attempted to leave him a generous bequest in her will, although Tiberius intervened to prevent it. So, a personal connection, and no doubt Galba, as the first emperor to come from outside the Julio-Claudian house, saw some propaganda value in an explicit association with the overthrown dynasty.

VESPASIAN

Denarius

Mint: Lugdunum.

Date: 71 (I’ll pass over the reasoning here).

Legends: IMP. CAE[S]AR VESPASIANV[S] AVG. TR. P. / TITVS ET DOMITIAN CAESARES PRIN. IVEN. (Imperator Caesar Vespasian Augustus, holding the Tribunician Power / Titus and Domitian, Caesars, the Princes of Youth)

Description: This is like the quintessential ideal of a Roman coin – the reverse given over to a blunt and inartistic political message. Here Vespasian proudly displays his sons Titus and Domitian (rather crudely rendered, the lower folds on the toga especially). They sit on senatorial curule chairs, and wave branches – whether olive or laurel is unclear but, in the aftermath of the Jewish victory, the reading would have been the same either way. A couple of interesting epigraphic items arise. “Caesares” is given in the plural – that is, employed as a title and not a name. That “the youth” could simultaneously have two First Men reads a little strangely, but it had distinguished precedent – on his exhausting and poorly-centred later denarii Augustus gave both his nephews this singular honour. “Ivventvtis” here is abbreviated as “Iven” – a rare example of an abbreviation which removes intermediate letters instead of simply truncating the word. “Cos” for “Consvl” as the classic example.

This was described by the seller as an emission of the Rome mint, but in fact this was produced at Lugdunum. An easy mistake to make – Rome issued the same reverse type with the same legend, and by Lugdunese standards this portrait is rather bland. The critical factor is the obverse legend – at Rome, this reverse was never combined with a “Tr. P.” obverse. So far as is known, anyway.

DOMITIAN

Denarius

Mint: Rome, naturally

Date: 1 January – 13 September 88

Legends: IMP. CAES. DOMIT. AVG. GERM. P. M. TR. P. VII / IMP. XIIII COS. XIIII CENS. P. P. P. (Imperator Caesar Domitianus Augustus Germanicus, Pontifex Maximus, holding the Tribunician Power for the 7th time, / hailed Imperator 14 times, Consul for the 14th time, Perpetual Censor, Pater Patriae)

Description: Domitian’s coins are rather fussy about his titulature, which is handy for us moderns. As a result, this can be dated closely. His 7th tribunician year ran from 14 September 87 to 13 September 88, and his 14th consulship from 1 January to 31 December 88. He received his 14th imperator-ship, for reasons apparently unknown, sometime in 86, and his 15th sometime in 88, also for reasons unknown. If we knew when the 15th was conferred, we could probably narrow the date down even further, but we don’t seem to have much of an idea. “Censor” is a rare title on the coinage, reintroduced by Vespasian as part of his program of cleaning up Roman morality after the debauches of Nero and Vitellius. Domitian took a total of 17 consulships, which was seemingly considered rather grandiose: his successors tended to stay in the low single figures. The portrait I think is striking – the features have more of a craggy “Flavian” quality, at least to my eyes, than the typical Domitian head. On the reverse we have the usual figure of Minerva, here quite well-proportioned.

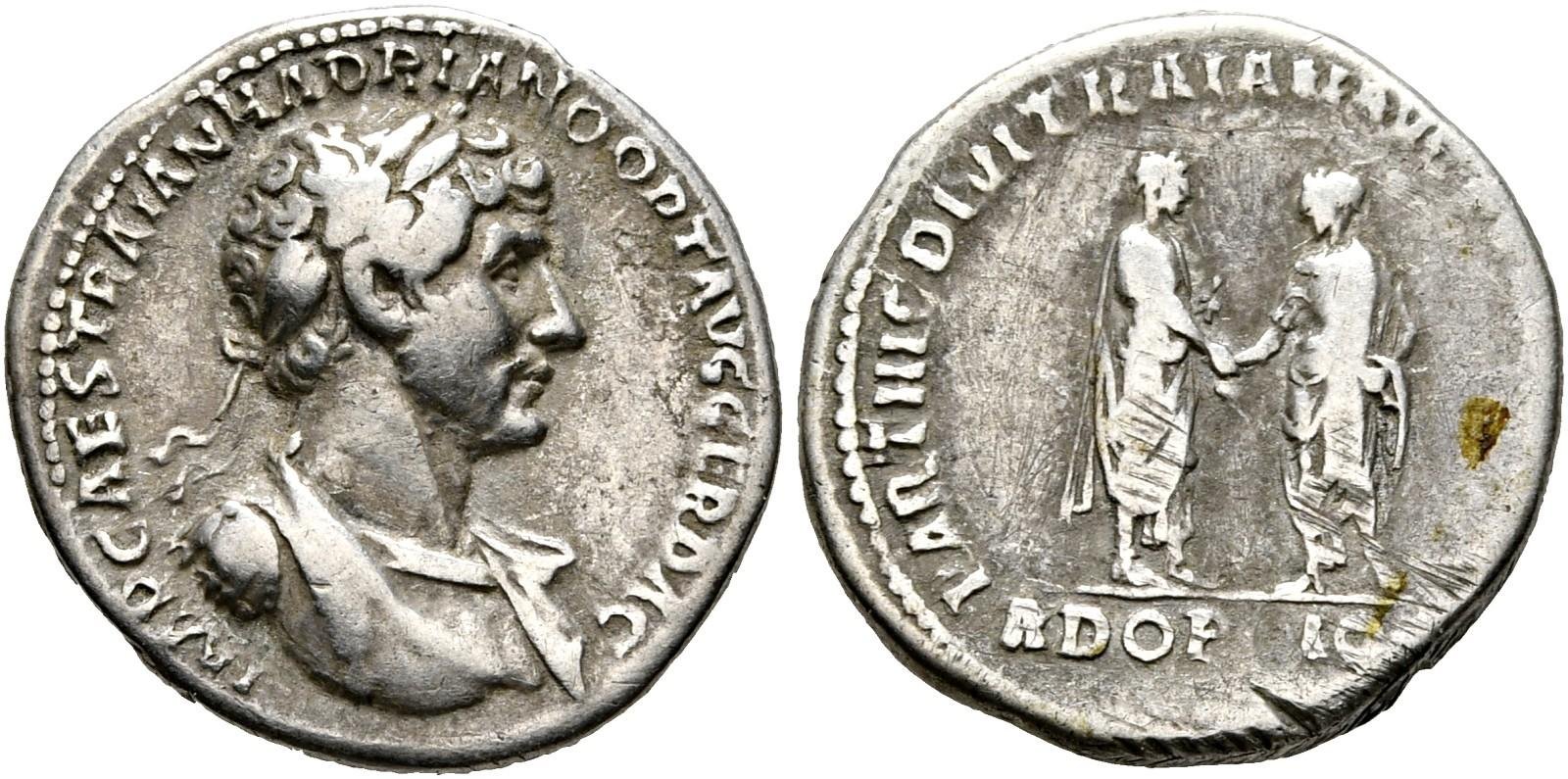

HADRIAN

Denarius

Mint: Rome.

Date: c. August 117.

Legends: IMP. CAES. TRAIAN. HADRIANO OPT. AVG. GER. DAC. / PARTHIC. DIVI TRAIAN. AVG. [F. P. M. TR. P. COS. P. P.], ADOP[T]IO in ex. ([to] Imperator Caesar Traianus Hadrianus Optimus Augustus Germanicus Dacicus / Parthicus, son of the divine Traianus, Pontifex Maximus, holding the Tribunician Power, Consul, Pater Patriae)

Description: The mysteries around Hadrian’s adoption are well-known – whether Trajan repented of his past indecisiveness on his deathbed, or the entire matter was a contrivance between Plotina and Hadrian after Trajan’s death (etc.). At any rate, contemporary eyebrows must have immediately been raised, as Hadrian felt obliged to use his very first reverse type to confirm the official story: Trajan passing the rulership of the world to P. Aelius Hadrianus with an amicable handshake. The second reverse type, shown here, sharpened the message further by adding an emphatic “ADOPTIO” below the scene. Trajan, it should be noted, is the figure on the left – I somehow see something of his features even on this rather worn specimen, though that may be wishful thinking.

As a very early coin of Hadrian, this bears his earliest, “uncorrected” titulature. As well as the standard imperial titles, Hadrian is also attributed the honours voted to Trajan – the three victory titles of “Germanicus”, “Dacicus” and “Parthicus”, and the lofty awards of “Pater Patriae” and, most conspicuously of all, “Optimus Princeps”. At some point, probably around mid-October (per RIC II), these titles were all removed from the coinage. The traditional explanation for their removal is Hadrian’s modesty: he, being away from Rome at the time he assumed the purple, was unaware that the fawning senate had granted him these lofty honours. As soon as he found out, he rejected them, wishing to assume such titles only when he felt he had deserved them. And, indeed, he took, or re-took, the title of Pater Patriae in 125.

There is, however, evidence to support a strikingly different explanation of the change in titulature. By chance, an announcement of Hadrian’s accession, dated 25 August 117, has been preserved in an Egyptian papyrus cache. It reads:

“…Be it known to you that for the salvation of the whole race of mankind the imperial rule has been taken over from the god his father by Imperator Caesar Traianus Hadrianus Optimus Augustus Germanicus Dacicus Parthicus. Therefore we shall pray to all the gods that his continuance may be preserved to us for ever and shall wear garlands for ten days…”

As RIC II notes, this text is dated just two weeks after Hadrian’s accession. It seems much more likely that the news of Hadrian’s accession would have arrived at Egypt directly from his camp, and not via Rome. If so, this suggests that the “large titulature” was something Hadrian adopted on his own initiative, and his renunciation of it a short time later was for a reason unconnected to his supposed modesty. Perhaps the situation was entirely inverted – he granted himself these honours without senatorial approval and, once news of this reached Rome, there was enough of a backlash among senators that he was persuaded to un-grant himself them. But this is all speculation.

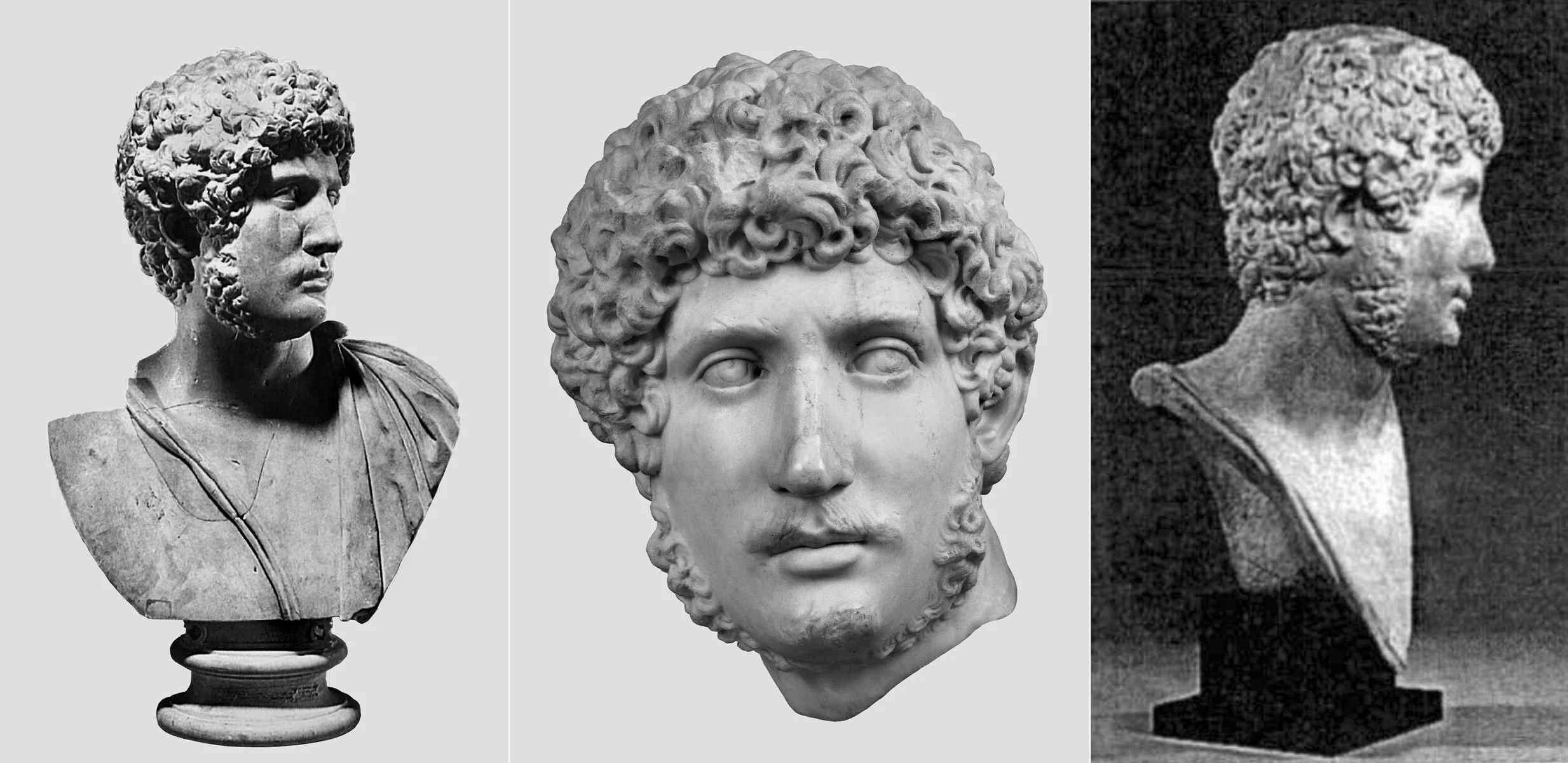

Anyway, to get onto the portrait. the portrait. Hadrian’s first heads tend to have a sort of sketchy, nervous quality to them, which I find immensely charming – they’re attractive in their own right, and eloquent of a mint having suddenly to pick up a new likeness after two decades of complacency. A particular feature of the earliest portraits is their smallness – they pick up directly from the last depictions of Trajan, where the head was shrunken to accommodate a deep heroic torso. Hadrian’s first issues follow accordingly: we tend to see small, somewhat fussy heads set on deep busts, often with long necks intervening. This head, to me, stands out from the typical depiction – despite being attached to a reasonably sized bust, the head is large, with calm and confidently drawn features. The hair is equally noteworthy – a tightly curled style instead of the usual combed-forward one. The coin portraits of Hadrian from before his return to Rome, despite the idiosyncrasies I’ve noted, are still legibly the man himself – although he was absent on campaign, campaign it seems the die-cutters weren’t forced to guess what he looked like. Probably not surprisingly – he was well established in public life and we may imagine he sat for an official portrait sometime during his first consulship in 108, at the very least. This makes the off-model hair on this coin rather curious – perhaps simply a strange whim of the engraver.

HADRIAN

Aureus

Mint: Rome (naturally).

Date: the legend configuration (COS III P P on reverse) puts this into the group of coins RIC II.3 dates to 129-130. An earlier belief that these were among the first issues of Antoninus Pius is no longer credited.

Legends: HADRIANVS AVGVSTVS / COS. III P. P.

Description: Mattingly, correctly, regarded this portrait die as one of “exceptional beauty and distinction”. To talk about this coin, I first have to talk about a different item completely. We have a few specimens (of varying degrees of preservation) of an exceptionally unusual bust type of Hadrian. The type is unquestionably ancient (one was dug up, under controlled conditions, from the “Egyptian room” of Hadrian’s villa) and the identification with Hadrian is also certain. We see a completely new image of Hadrian – a young man, with thick sideburns instead of the familiar beard, and dense curly hair instead of a brushed-forward style. The head, twisted to the left, is set on a “heroically nude” torso, with a twisted sword-strap over one shoulder. The use of a “heroic torso” is not unique or new to this bust: Trajan, for example, depicted himself in the same manner. But the employment of a wholly new portrait, with little resemblance to the imperial propaganda-head circulated all over the empire on statues and coins, is without precedent. Nor, indeed, was it followed up on for some time to come.

Various explanations of the bust have been offered. In short, the most convincing is that the bust is meant to resemble Kresilas’ celebrated statue of Diomedes, and thus assimilate Hadrian with that legendary personality. The angle of the head, the facial hair, and the baldric over the right shoulder are all points in common.

Diomedes was, perhaps, not a central figure of the Roman national mythology – but it was his theft of the Palladium which caused the fall of Troy, an event which led, eventually, to Aeneas arriving in Italy. Moreover, the Palladium itself was regarded, in Hadrian’s day, to be residing in Rome and exercising its protective powers over the city just as it had done to Troy. So Diomedes could be regarded as a “patriotic” figure, suitable for assimilation to the emperor. The use of a relatively obscure Greek figure, meanwhile, could perhaps have been an articulation of Hadrian’s intellectual and philhellenic qualities. On a more general level, syncretism with a youthful hero projected an image of energy and virility suitable for the commander-in-chief.

The identification with Diomedes is however uncertain, although it is the strongest hypothesis. Other ideas include:

syncretism with Romulus (I think this is unlikely, as it fails to accord with any other depictions of Romulus, especially those on Hadrian’s coinage);

syncretism with Antinous (would be lovely if this were true, and the portrait was found in Hadrian’s shrine to him);

Hadrian symbolically rejuvenated via his participation in the Eleusinian Mysteries (this would need an enormous digression to explain fully, but in short it’s not today believed that he depicted himself in this way, either via this bust or more generally); and

Hadrian syncretised with Augustus as a reborn “second Augustus”.

No doubt there are others.

Anyway, with that preamble out of the way: the coin itself. It’s entirely accepted today that this coin-portrait is intended to be a translation of the “heroic bust”, and so the foregoing observations about the symbolism of the bust all also apply to the coin.

This type of portrait was attached to a number of different reverses – all very rare. It first appeared on this coin, in 129/30, was employed most heavily in 130, and then made a final reappearance in 136. In short, I have no obvious ideas as to why the portrait might have appeared numismatically when it did: it coincides with no imperial anniversaries or other notable events. So I’ll skip over this in silence.

Some of the reverses allude to the founding of Rome, and its patron deities: we see Romulus, Jupiter Victor and Venus Genetrix. These types perhaps, vaguely, support the idea that the portrait is intended to recall Diomedes. Other reverses are more personal to Hadrian: him as a hunter on horseback (“VIRTUTI AUGUSTI”) and the deified Trajan and Plotina.

And, then, this rather enigmatic reverse here. Hadrian, in military uniform with standards. His hand is raised, as if giving an address, although it isn’t quite the outstretched arm typical of the adlocution. How this reverse complements the portrait is less obvious – perhaps, as suggested above, the iconography of the youthful hero was regarded as an appropriate match for the emperor in his role of imperator.

This reverse was never employed by Hadrian on his coinage outside of these aurei with the youthful portrait. The reverse however appears on certain bronze medallions of Hadrian, which can be dated to the same 129/30 period as this coin, based on the arrangement of the legend. RIC II.3 speculates that these medallions, considering the military imagery of the reverse, were given out to soldiers or officers on some suitable occasion or other. Perhaps this aureus (and the other aurei in the youthful portrait series) were also “medallions”. There is further convergence between the youthful portrait aurei reverses and medallions – we possess also medallions with “ROMULO CONDITORI” AND “VIRTUTI AUGUSTI” reverses, in both cases with identical types to those used on the aurei.

Perhaps, then, tying the strands together – some kind of grand military occasion in 129/30, with a number of soldiers and officers being honoured. Most receiving bronze medallions but a select few (perhaps, philhellene cognoscenti close to Hadrian, who would be intellectually tickled by the Diomedes reference) receiving the aurei. All speculation, of course, but interesting to consider.

PS: the “emperor/standards” reverse, which made its debut here, was not repeated by Hadrian’s successors. It however reappeared in the 3rd Century as the stock “prince of youth” reverse type, a position it maintained into the Constantinian era. Why this was –and whether some connection can be drawn between its later association with the “youth leader” and its initial association with the artificially youthful Hadrian– I do not know.

HADRIAN

Denarius

Mint: Rome.

Date: 130-133

Legends: HADRIANVS AVG. COS. III P. P. / AFRICA (Hadrianus Augustus, Consul three times, Pater Patriae)

Description: BMC plate coin! I have a very deep, not wholly rational affection for the venerable BMC – nobody prefers it over RIC, but, it was the first serious numismatic work I ever read, and both its insights and its lapidary prose made a great impression on me. Also a fairly antique provenance, as I shall explain.

Fairly little to say about the coin itself – it’s a dignified but unexciting late Hadrian head, and on the back we have the personification of “Africa”, part of the well-known “provinces cycle” of Hadrian’s later coinage. By this stage the tendency, as here, was to cram the entire name and titulature onto the obverse, to leave the reverse entirely free for descriptive text. Anyway, the coin’s subsequent history. This was in the Bank of England’s collection by 1865, in which year the collection was loaned to the British Museum. The collection was transferred to the Museum outright in 1877. This coin went on to appear in the 1936 Coins of the Roman Empire in the British Museum, Volume III. The Museum parted with the coin in 1959, as part of a trade with one G. R. Arnold – what they got in return, I sadly do not know. The coin entered trade in 1969 when Arnold’s collection was auctioned off; and today it resides in the author’s collection. Where it’ll go next, I might wonder.

HONORIUS

Nummus

Mint: Rome. The mint-mark is off the flan, as is typical, but Rome was the only mint to use this design, so the identification is certain.

Date: RIC X dates this to between 408 and 423. I follow this without comment.

Legends: D. N. HONOR[I]VS P. F. AVG. / [GLORIA ROMANORVM] (Our Lord Honorius, Pius, Fortunate Augustus / the glory of the Romans)

Description: really just a terrible coin. On the obverse a rough portrait, and the lettering, uncommonly legible, is crude and uneven. The reverse is a mess: the legend is almost entirely off-flan and the type (the emperor restraining a captive with one hand, and accepting the homage of a suppliant with the other) is crudely executed – though, again, it’s uncommonly clear on this specimen. The dramatic irony arising from the chasm between the image of military potency presented here, and the reality of foreign policy failures and a deteriorating economy served by gruesome coins like these, requires no elaboration.

TUSCANY

Giulio

Mint: Florence

Date: 1571 – the date is actually on the coin! No need to squint at uncertain passages in the ancient authorities in the hope of producing, at best, a tenuous “circa”.

Legends: COS• M• MAGNVS• •DVX• ETRVRIÆ• 1571• / DIVIS• IOA• B• PRO• ET• COS• CONS• (Cosimo de Medici, Grand Duke of Tuscany / Saints John the Baptist, protector, and Cosmas, conserver)

Description: An attractive reverse, I think – the work of Pietro Paolo Galeotti, a competent medallist of the day. We have Saint John and Saint Cosmas walking forward in the midst of some disputation, a scene not wholly unreminiscent of the famous central pair in Raphael’s School of Athens. John the Baptist was the patron saint of Florence, centre of Medici power – Saint Cosmas is a much obscurer figure and no doubt he owes his appearance here to the duke being his namesake. “Sanctus” is the traditional rendering of “Saint” in Latin – “Divus”, as here, is a bit of precious classicising, as is “Etruria” for Tuscany on the obverse. That side has little going for it, the ugly Medici arms (none of the fun weirdness of the Visconti) and a radial crown of some sort.