UNIFORMS AND INSIGNIA OF THE CENTRAL AFRICAN EMPIRE

The Armed Forces, Imperial Guard and Gendarmerie

Photo 1. 6 March 1975 — Bokassa triumphantly welcomes Giscard d’Estaing to Bangui. The “Bangui Conference” was, in hindsight, the apex of Bokassa’s credibility as a world statesman. Several uniforms on show here. From left: (1) Mobile gendarmerie sergent in khaki service dress [see Fig. 48]. (2) Police general [see Fig. 58, next page]. (3) Imperial Guard sous-lieutenant or lieutenant [see Fig. 25]. (4-5) Two mobile gendarmerie officers in camouflage parade/service dress [see Fig. 49]. (6) Infantry officer in service dress [see Fig. 9]. (7) Bokassa, in civilian clothes, wearing the badge of the MESAN on his lapel. (8) This mysterious figure — possibly a naval officer? See the section on the navy below. Photo © AGIP / Bridgeman Images, used with permission.

Preliminary Remarks.

Organisation

This, I think, isn’t unimportant. “World Armies” by John Keegan and others, which was published right at the end of the Bokassa era,[1] gives the organisation of the CAE armed forces as follows.[2] This is the only such description I can find anywhere.

The army: 800 men, organised as one infantry battalion plus support elements. We’re told that, under Bokassa, the “size of this battalion has been increased”.

The air force: 100 men.

The gendarmerie: 500 men.

The Imperial Guard: 700, some of whom are women.

In Keegan the infantry battalion is described as being mostly posted at Bouar (about 230 miles from Bangui, as the crow flies), the Imperial Guard at Bangui. Other accounts put the Imperial Guard at Berengo, Bokassa’s private estate near Bangui, and this is certainly a plausible place for them.

Some problems arise here. I have seen two unit colours with legible inscriptions, and these identify themselves as the colours of:

The “1st Infantry Battalion” – carried by an infantry unit.[3]

The “2nd Battalion, Berengo” – carried by the Blue Honour Guard (see part 3 for my taxonomy of the honour guard units) at Bokassa’s coronation.

It would seem to me that, if there was only one infantry battalion (per Keegan), it wouldn’t need to identify itself as the first infantry battalion – accordingly, this usage seems to imply (at least) a second infantry battalion.[4] Meanwhile, the “2nd Battalion” colour doesn’t identify itself with the infantry. The question then, I think, is whether this is an infantry or an Imperial Guard colour. It doesn’t identify itself with the Guard either, but it cites Berengo, where at least some of the Guard would likely have been stationed. Of course, a 2nd infantry battalion could also have been based there, the 1st remaining at Bouar.

I should note here that, in footage, I can see an infantry colour party carrying a flag of the “2nd Battalion” pattern, but it’s unclear whether it’s the actual 2nd Battalion flag, or another unit’s. I think, conceivably, the visible text is “[BA]TA[ILLON] / [BER]EN[GO]” —i.e., it is the 2nd Battalion flag— but I wouldn’t bet the farm on it. See the picture below.

© France 3 / Kilaohm / Gregory Laville.

To try to think this through. If it’s an infantry colour then we have at least two battalions of infantry. If it’s a Guard colour, then we have at least two battalions of Guard. If it’s a Guard colour, we can still have further infantry battalions, if take the view that the 1st Battalion flag implies the existence of further battalions. Which takes us to a minimum of four battalions. This conclusion could, perhaps, inflate the armed forces to improbable size – although, of course, these units need not have been at anything close to full strength. Another possibility, which I raise to disregard, is that the infantry and the Guard were on the same sequence — i.e. the infantry was the 1st Battalion and the Guard was the 2nd Battalion. I think the idea of the Guard being numbered lower than the infantry is unlikely; and my belief that the Guard developed from the police, and not the army, makes it unlikely that they’d be numbered in one sequence.

Regarding the size of the Guard, I would also note:

The “Dictionary of Overseas Operations of the French Army, 1963 – present”, which, of course, need not be correct, describes the French intervention force neutralising “the two battalions of the Imperial Guard at Berengo”.[5]

Brian Titley, in his biography of Bokassa, says the Guard were “one thousand men in all”, which would put them as somewhere above one battalion.[6]

A separate but linked question is, what was the Guard actually comprised of? Of course, its (male) infantry element. Keegan and elsewhere give it a female element, but, as I set out later, I hesitate to give the female unit to the Guard and not the regular army. The female unit wore a distinctive red and black ceremonial uniform, which is also seen on a large (male) band which is much in evidence at the coronation. If the female unit was part of the Guard then I think this band must also be. Which then prompts the question of what this band’s “day job” was – were the members civilian musicians who just turned up for ceremonies as needed, or were they actual full-time soldiers (whether of the Guard or the army)? I do not know.

I have found a single, out-of-the-way reference to a “1er Bataillon des Transmissions”, but it’s unclear from the context whether this was a Centrafrican or a French unit, perhaps the latter. An army this small certainly didn’t need an entire signals battalion, but the title of course need not have borne any particular resemblance to the actual size of this unit, if indeed it existed.

There was evidently, at one point, a navy — see its section below. This cannot have been large even at its height, and the fact that Keegan fails to notice it suggests it may have been disbanded by 1979. I have no idea whatsoever about the organisation of the air force — with only 100 men (Keegan) it can’t have been divided up too finely.

The gendarmerie was evidently organised into at least two “legions”, as the flag of the 2nd Legion is known.

The “Quartier-Général Jean-Bédel Bokassa”

A pucelle, inscribed thus [Fig. 7], is seen invariably(?) on generals and commonly, but far from universally, on infantry officers. “Other ranks” are also occasionally seen sporting one. The central device is an “all arms” emblem but, despite this, I’ve never seen it worn by an air force officer (with the caveat that these men are hard to find in the source material) or by the gendarmerie (assuming the grenade is a reference to them). The significance of this I do not know. No doubt the army had some kind of “general staff”, although one can’t imagine it had much to do on a day-to-day basis: the armed forces were not large, and presumably Bokassa’s whims could be exercised without regard to such chain of command as might be in place. The pucelles of the gendarmerie and Imperial Guard seem to have been genuine branch insignia, and were worn (or intended to be worn) by all ranks. Conversely, the army general staff cannot I think have been so large as to encompass the fairly large number of officers one sees with the "Quartier-Général” pucelle, and I’d imagine a true general staff had very little need for enlisted men. Which makes me wonder if this item was intended as something closer to an award — a sort of “honorary membership” of the general staff. But this is all speculation.

For some extra confusion, a flag seen in footage (see part 5) seems to identify itself as the colour of the "Quartier-Général”. This may indicate that the Quartier-Général was a discrete unit but, on the other hand, none of the colour party or the men following behind is wearing the “Quartier-Général” pucelle.

Incidentally, as well as being a discrete unit and/or a state of mind, the Quartier-Général was also a physical premises, whose entrance sign can be distantly glimpsed in 1975 footage.

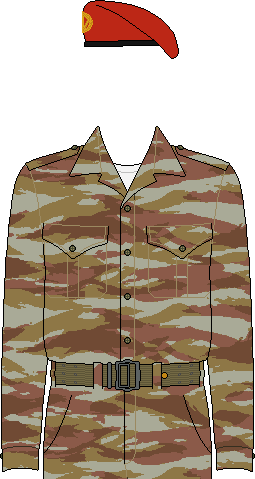

Camouflage uniforms, types

The photos suggest there were at least five types of camouflage uniform in use. I don’t wish to be too dogmatic on this point, as no doubt this is an area where the potential for manufacturing and shade variations was endless. But I would identify the below types as being meaningfully distinct from each other.

Type A. (e.g. Fig. 1) This was, essentially, the French “TTA 47” uniform — whether actual French surplus, or copies produced elsewhere, I don’t know and decline to guess. “Lizard” camouflage on a light greenish base. Usually solid base colour on the inside though possibly sometimes also printed on the inside. A four-pocket open-collared jacket. Pockets with pointed pocket flaps, the pocket bodies concealed. All buttons concealed except the shoulder strap buttons which seem to have been dark green plastic. The jacket is invariably seen with sleeves rolled up so details of the cuff are unknown. The TTA 47 jacket had tabs fastened with a button, so presumably that. Trousers with cargo pockets, other pockets invisible but presumably rear and side pockets also. Cargo pocket flaps straight with “clipped” corners and concealed buttons. I can’t find any photos where the belt loops of the trousers are visible. The TTA 47 trousers had six loops in the standard places, for comparison — not, I think, tall enough to fit a TAP 51 belt through.

Type B. (e.g. Fig. 25) The same as Type A except on a tan base. The inside seems to have always been solid base colour.

Type C. (e.g. Fig. 20) Seen from one specimen (in a 1979 photo) which seems to be very heavily faded – the base is a greenish grey hue and the brown and green elements are pale and greyish. The trousers are made out of two different, and visibly non-matching, rolls of material. I’d wonder if this wasn’t a local production, in view of its apparently lower quality. In the photo where this uniform appears the top half is tucked into the trousers, but from its bulk it appears to be a jacket rather than a shirt. Four-pocket open-collared design, pointed pocket flaps, buttons visible at the shoulder straps, breast pockets and cuffs. The breast pocket body seems to have been visible. The front opening and skirt pockets are unseen but presumably the buttons there would have been visible also. Buttons are dark green plastic. The trousers are tailored in a rather civilian-looking “flared” style, with rear (straight flaps with visible buttons) and side pockets but no cargo pockets. The trousers have tall belt loops for accommodating the TAP 51 belt. Low-quality 1979 footage shows a man wearing camouflage so faded it seems almost a single colour – perhaps from this “batch”.

Type D. (e.g. Fig. 2) “Lizard” camouflage: a tan base, the green parts relatively bright and the brown parts a distinctively bright, golden shade. The inside in solid base colour. The top half is noticeably short and is probably better described as a shirt than a jacket. Five-button front, the buttons seemingly snaps rather than buttons proper. Breast pockets with visible bodies, rectangular flaps with clipped corners and two snaps per flap. The skirt, so far as I can see, had no pockets. There were rectangular tabs inside the sleeves which, when the sleeves were rolled up, attached to a snap on the upper arm to stop the rolled-up part from unrolling. I don’t think I can see any of these shirts with shoulder straps but I don’t rule out some having had them. In the absence of shoulder straps rank slides were worn on the sleeve retaining tabs (both officers and men). Trousers with cargo pockets, side pockets and presumably rear pockets also.

Type E. (e.g. Fig. 4) As Type D except in “leopard spot” camouflage: light and dark brown on a light greenish base. The interior solid base colour. Certainly some of these shirts had shoulder straps, although they don’t seem to have been widespread.

Rank Insignia

Rank insignia, apart from two exceptions I note in the text, were after the French model. I assume, if you are reading this, you know what French rank insignia looks like.

The overall appearance of the military

A point to be kept in mind is that the source material almost invariably shows the CAE armed forces in non-combat situations, and a very high proportion of these situations are parades, reviews, etc., plus of course the coronation. Unsurprisingly, the men we see in these settings are generally well turned out. On the few occasions we see “mobilised” soldiers (and these all, I think, relate to either the overthrow of Bokassa or the immediate aftermath) they appear much more chaotic – combinations of camouflage and fatigues, a great variety of headgear, etc.

MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS

When did the peaked cap replace the kepi? The peaked cap seems to have come in early for the army – I have some difficulty establishing the exact start date but Bokassa can be seen wearing one in footage taken in the aftermath of his coup (i.e., 1966) so, unless he brought it in immediately, it must have pre-dated him. The gendarmerie seem to have still worn kepis in February-March 1975, but by May 1976 they were all in peaked caps. The mobile gendarmerie seem to have held onto their kepis until after the coronation. More dated photos/footage would help clarify this. The air force seem to have always worn peaked caps, in line with French practice.

Tunic pockets. The top half of the service/”vareuse” uniform was a khaki four-pocket open-collared tunic. These seem to have varied somewhat in the arrangement of their pockets. The most common design was rectangular pocket flaps with the pocket bodies hidden. However breast pockets with pointed flaps (either three points or one point with rounded corners), with or without visible bodies (if visible, pleated) can also be seen. Skirt pockets seem to have always had rectangular flaps but sometimes the body is visible, if so it seems to have always been unpleated.

Buttons. Gold and silver buttons seem, at least in some cases, to have borne devices. The source material is rarely clear enough to permit identification, unfortunately. I therefore pass over this topic in silence and I haven’t attempted to draw devices on the buttons in the illustrations. Exceptions: Bokassa’s own buttons show an upright sword with an oak branch on the left and a laurel branch on the right. This is the same scheme as the infantry beret badge, so probably safe enough to assume this was their pattern also. The gendarmerie button displayed a bursting grenade, naturally enough.

Medals. These are an entire topic in themselves, which I don’t propose to get into. There’s a very handy reference here, and I’ve drawn medals, based on this, where they’re needed to complete illustrations. But nothing here is intended to be an exploration of the medals, the circumstances of their wear, etc. The ribbon bars are a generic mix of French and CAE awards and are for purely indicative purposes. In neither case have I tried to be inaccurate, but neither have I been extremely concerned with accuracy, in view of the extreme tediousness of drawing and checking these. Jump wings were widely worn above the right breast pocket, at varying distances from the top. Design seems to have been identical to the contemporary French parachute badge — one or two seem to have been entirely gold but, absent any decisive evidence to the contrary, I’ve coloured them all predominantly silver, after the French manner. These are seen mostly in metal though at least one appears which is embroidered on a black backing. There was no parachutist unit in the army (though one had been formed by the mid-1980s) so it’s unclear to me where and how parachute training was done.

Aiguillettes and fourragères. These tended to be worn somewhat carelessly, especially the narrow cords on the aiguillette which can be found in all sorts of non-standard arrangements.

The Infantry.

Fig. 1. Caporal-chef, Infantry, 1970.

Fig. 2. Officer, Infantry, 1977,

Fig. 3. Soldat, Infantry, 1977.

Fig. 4. Sergent-chef, Infantry, c. 1977.

Fig. 5. Infantry beret badge.

Fig. 6. Infantry cap badge.

Fig. 7. “Quartier Général” pucelle.

Fig. 8. Infantry (army?) sleeve shield.

Parade dress (“prise d’armes”). [Figs. 1-4] Camouflage uniforms of Types A-E, without t-shirts. Type D is much in evidence at the coronation. Type E is a late appearance, and not until after the coronation probably. Red berets with the usual badge [Fig. 5] or helmets. Black boots. Gloves sometimes worn, colour parties also with gauntlets. Greenish pistol belts of French “TAP” type. Berthier carbines may have been retained for “present arms” neatness after AKs were introduced. Footage of a parade circa 1977 shows men in Type C uniforms, with helmets, preceded immediately by men in Type C uniforms with red berets, whatever the distinction signifies.

Parade dress (“prise d’armes”), insignia. The “Quartier Général” pucelle [Fig. 7] (see commentary in the preamble) sometimes appears. A fourragère, seemingly yellow, was used at some point. It can be seen in 1970, worn on the left shoulder by all ranks. One officer seems to be seen wearing one on the right shoulder, in 1975. By 1977 they seem to have disappeared. Officers seem to have worn their rank bars directly on their shoulder straps without slides. An officer driving Bokassa’s vehicle at the coronation wears curious “home-made” looking gold-trimmed shoulder straps with a single silver bar added [Fig. 2] – whatever rank that may have been intended to indicate. The position with the men’s rank insignia is much less clear – seemingly these were worn on the left upper arm (simply as chevrons on a backing rather than a full ecusson with central device after the French manner) but more evidence is needed. One man in Type D uniform I think may be seen, distantly, with a NCO rank slide on his sleeve retaining tab.

Fig. 9. Commandant, Infantry, 1975.

Fig. 10. Capitaine, Infantry, 1969.

Fig. 11. Bokassa’s aide-de-camp, 1976.

Fig. 12. Infantry shoulder board.

Fig. 13. Infantry sleeve title.

Fig. 14. Infantry (army?) collar patch.

Fig. 15. Trouser stripe on the “winter” service dress.

Service dress (“tenue vareuse”) (officers). [Fig. 9] Khaki four-pocket open-collared tunic. Generally these are a consistent mid tan, as shown here, but one figure can be seen with a very light shade (with cap of the shade shown here). Silver tie-clip of unclear design – a vertical central element with long horizontal extensions. Tan trousers. Black shoes. Tan peaked cap as illustrated. The chinstrap, gold, can be seen in perhaps as many as four different styles: two parallel cords in classic German style; the same but with the two cords intertwined; a single broad cord in “twisted” style; and possibly also a rectangular strap similar to a kepi chinstrap. The four styles seem to have, at least for a time, been worn interchangeably, and as far as I can see an officer’s rank didn’t determine the style used. Further evidence needed.

Service dress (“tenue vareuse”), insignia (officers). Embroidered cap badge as illustrated [Fig. 6]. Black full detachable shoulder boards with rank stripes below a gold sword pointing upwards [Fig. 12]. At the top of the left shoulder, a dark shoulder arc with embroidered border and text. This, eventually, read “EMPIRE CENTRAFRICAIN” in gold on black, as illustrated [Fig. 13], but it can be seen in photos which pre-date the establishment of the empire. On an auction site I’ve seen a shoulder arc (no date supplied) of the same pattern as Fig. 13, reading “ARMÉE CENTRAFRICAIN” in silver on a dark blue background. But this could date from the post-Bokassa era, where one also sees shoulder arcs worn. A shield on the upper left shoulder as illustrated [Fig. 8]. Black pentagonal collar patches as illustrated [Fig. 14]. The “Quartier Général” pucelle sometimes seen [Fig. 7]. One officer seen next to Bokassa on several occasions (perhaps his aide-de-camp) wears a yellow fourragère at the left shoulder [Fig. 11].

Service dress (“tenue vareuse”) (officers, “winter” version). [Fig. 10] As regular service dress but seemingly made of heavier material and in a noticeably greyish shade (the same as the French “terre de France” uniform of the day – French officers so dressed can be seen in the same photo and the colour is identical). Breast pockets with single-pointed flaps and pleated bodies, skirt pockets with bodies. Black piping on the side seam of the trousers with a broad black stripe on either side. I have only seen this uniform worn by CAE officers on trips to France, and possibly that was its specific purpose.

Khaki service dress (officers). I have never seen this but I assume it must have existed, details as per enlisted men (immediately below). I would imagine officers wore the beret and not the peaked cap.

Fig. 15. Soldat, Infantry, 1977.

Fig. 15A. Soldat, Infantry, 1977.

Khaki service dress (enlisted men). [Fig. 15] Not commonly seen. As far as I can see, a khaki shirt with long sleeves (seen rolled up and down) worn open at the neck. Pleated breast pockets, buttons unobtrusive khaki-ish colour, tucked into khaki trousers. US-style narrow khaki trouser belt with solid buckle. Worn with red beret. Shield worn on the upper-left shoulder. Black full detachable shoulder boards with rank insignia below a sword, red for enlisted men and gold for NCOs [Fig. 12] [7]. Unclear if a pucelle was worn. One figure, in partial contrast to the above, can be seen with a khaki beret and no arm shield — but the red sword devices on his shoulder straps are clearly visible [Fig. 12A]. Two figures can be distantly glimpsed in 1975 footage dressed like Fig. 15, but with yellow aiguillettes, of unclear arrangement, on the left shoulder, and a shoulder arc above the sleeve shield.

Fig. 16. Soldat, Infantry, 1970s.

Fig. 18. Sergant, Infantry, 1975.

Fig. 19. Soldat, Infantry, 1979.

Fig. 20. Soldat, Infantry, 1979.

Fig. 20A. Soldat, Infantry, 1979.

Camouflage/fatigue uniform. [Figs. 16-20A] Camouflage uniforms of Types A-D, or plain olive drab or khaki fatigues (or a combination). The jacket occasionally tucked into the trousers. T-shirts of various colours sometimes worn under the jacket: white seems to have been the regulation. The red beret was worn (I have seen the khaki beret here also), but also generic peaked fatigue caps (solid colours) and sharply sloped camouflage caps in “Bigeard” style — the latter may have been phased out as they aren’t seen in later footage. Black boots. TAP Belts. "Quartier-Général” Pucelles occasionally seen. See the note in the introduction for some remarks on how these men appeared “in action”.

Camouflage/fatigue uniform, insignia. Same comments as for parade dress as regarding rank insignia. "Quartier-Général” Pucelles intermittently worn by officers and enlisted men. I think I see one sleeve shield and no doubt they appeared from time to time. Based on the limited evidence available to me, there seems to have been a trend for plain fatigue uniforms to be a bit “dressier” as regards insignia, at least in the mid-70s, compared to camouflage uniforms. For example, a single (black-and-white) 1975 photo shows one man in solid colour fatigues with beret, rank slides, EMPIRE CENTRAFRICAIN sleeve title and sleeve shield. One officer of this period seems to wear his rank bars, on a backing, above (and touching) his sleeve shield.

Berets. Red was the infantry or army colour, and is the colour overwhelmingly seen. Khaki berets appear very rarely — I’ve seen them twice (in 1977 and 1979 footage) and maybe once again in a black-and-white photo. The shade is too light to be confused with the Imperial Guard beret.

Fig. 21. The mysterious helmet. © the Institut National de l'Audiovisuel.

Fig. 21A. Another type of helmet. © William Karel / Getty Images.

Helmets. There was evidently more than one model in use — this is fairly obscure. The standard helmet seen at the coronation [Fig. 21] is frustratingly elusive – I’m not a helmet expert, granted, but I’ve undertaken a degree of searching which has turned up nothing. If anyone can bail me out here I’d be most obliged. French model 1951s also seen, as well as what seems to be a French police or gendarmerie helmet of some ‘50s or ‘60s model, with the comb and front badge removed, and painted green [Fig. 21A]. Possibly also Gueneau helmets, the badge I think(?) painted the same colour as the helmet — though the men wearing those may be police.

Equipment. AK rifles of various designs, antique Berthier rifles and carbines. Presumably also MAS-36s and MAS-49s although I haven’t seen them. One man can be very distantly seen with one of those long-barrelled AK models. Belt equipment is frustratingly elusive. If they received AKs I think it’s safe to assume they received the standard Soviet khaki fabric pouch at the same time, but I’ve never seen one of these on camera. I have also never seen a canteen, of any model. One single man is seen with some sort of small canvas or web material shoulder bag.

The Female Soldiers.

General remarks. There was at least one unit of women in the CAE army. This is universally (including in Keegan, quoted at the top) described as being part of the Imperial Guard. I’m unsure if this is correct. The female service uniform (which doubled up as a parade uniform before the introduction of the red uniform) was a textbook infantry uniform – red beret with infantry badge. Type A camouflage jacket, sometimes with "Quartier-Général” pucelle. Camouflage shorts were worn, with low boots and khaki socks turned up over the tops. Less can be determined by the red parade uniform but, again, this included a red beret. They could perhaps have been part of the infantry organisationally but “brigaded with” the Imperial Guard in terms of, being quartered at Berengo and carrying out whatever duties the Imperial Guard did.

Fig. 22. Officer, Infantry, 1970.

Gender of officers. A single female officer in modified army “tenue vareuse” can be seen in 1970 footage [Fig. 22]. 1975 (or circa) photos show a male officer. The position is (so far) impossible to ascertain re: the red uniforms.

The IMPERIAL GUARD.

This is a difficult matter, perhaps surprisingly so, and I would hasten to emphasise that everything I set out here is pure guesswork.

The Guard was, we read, formed in 1965 by Bokassa’s predecessor David Dacko – its title then is unknown to me but the “Presidential Guard” is the immediate guess. At its formation it numbered 120 men.[8]

To completely excise what was, in earlier drafts, several dense paragraphs – I believe, in short, that the Guard started out wearing police (or, at minimum, police-style) badges [Figs. 23-24]. And, from this, some sort of organisational relationship to the police, at least to begin with, is probably a necessary implication.[9] I lack the clear colour photos which would make this certain, but I believe the preponderance of evidence suggests that this was the insignia used by the Guard up to the time of the coronation, or thereabouts.

Fig. 23. Imperial Guard beret badge.

Fig. 24. Imperial Guard pucelle.

Fig. 24A. A later, different, Imperial Guard pucelle(?) © Getty Images / Daniel Simon.

I’ve gone back and forth on the colour of this insignia — I believe more likely than not it was gold (and, certainly, the modern Centrafrican police badges are gold) but it certainly does appear silvery in many photos. More evidence is needed.

We see the Guard out in force at the coronation (December 1977). By this point they’re kitted out entirely with Type E uniforms (this is the earliest datable appearance of those) with brown berets. They seem to all be lightly-armed, with Uzis and pistols, while infantry on the same occasion carry AKs, older rifles, and sometimes wear helmets. They share crowd control duty with the infantry to an extent, but they’re also seen taking up various positions close to Bokassa, to which the infantry has no comparable role. The insignia picture is bewildering. All enlisted men and probably some officers seem to have no beret badge at all, while a few (all officers?) wear the standard gold infantry beret badge. One officer seems to wear a “police style” pucelle, and the others I can see seem to have had none. Likewise the enlisted men, except one man who seems to be wearing a "Quartier-Général” pucelle pinned directly to his jacket above the right pocket. One officer is seen wearing rigid black shoulder boards, on which there is standard rank insignia but no device.

The police-style insignia however seems not to have been wholly replaced, as it reappears in a photo dated 24 September 1979 (i.e., a few days after Bokassa’s overthrow). The significance of this I cannot guess.

It feels very odd to me that the insignia of this supposedly elite unit should be so haphazard, and lacking a distinctive device, but this is what the evidence suggests. Perhaps –and this is entirely speculation– the Guard was caught in the middle of expansion at the time of the coronation, from its original “close security” role to the thousand-strong rival to the army it eventually became. There was perhaps some command to switch from police style insignia to army insignia, reflecting the new role of the Guard as a paramilitary force, but the additional order of insignia had failed to arrive in time and so the Guard had to go without, except for a few men who either continued to wear their police insignia or had managed to find army insignia. Perhaps the “replacement” insignia, whatever it was, simply never turned up, and the Guard went back to the police style.

I should note that the only men I can confidently identify as Guard are all wearing camouflage or fatigues and berets. That is – I cannot locate any Guard wearing service dress etc. This is a perplexity but, absent any evidence, for the moment it is what it is.[10]

Incidentally — for some reason I find it a little difficult to distinguish between gold and silver in many photographs and footage, but especially with regard to these men. I believe the badges and rank insignia were gold but I may be incorrect.

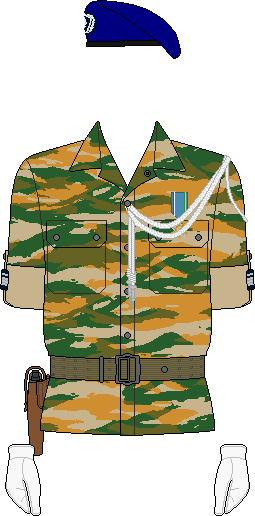

Fig. 25. Sous-Lieutenant, Imperial Guard, 1975.

Fig. 26. Commandant, Imperial Guard, 1977.

Fig. 27. Soldat, Imperial Guard, 1977.

Fig. 28. Sous-Lieutenant, Imperial Guard, mid-1970s.

Fig. 29. Soldat, Imperial Guard, 1977.

Parade (“prise d’armes”) and/or duty/fatigue/etc. uniform. [Figs. 25-29] These categories seem to have overlapped somewhat in practice. The “pre-expansion” Guard seem to have worn Type A and B uniforms initially [Fig. 25], or solid greyish green (sometimes rather dark) fatigues [Fig. 28], but by the coronation the Guard was overwhelmingly in Type E [Figs. 26-27]. A few Guardsmen on crowd control duty at the coronation can be seen in greyish-blue fatigues, of identical hue to the fatigues worn by the police — further evidence, I must suppose, for the police connection [Fig. 29]. Rank worn on either slides or (sometimes for officers) full detachable black shoulder boards. Rank stripes for officers seem to have been gold. Beret badge [Fig. 23] and pucelle [Fig. 24] both of somewhat uncertain design – see the above commentary for some rambling on this question. Some enlisted men seem to have had pucelles also. A single figure who I think may be Imperial Guard wears light fatigues, beret, and a pucelle as Fig. 24A. If not Imperial Guard then it is unidentified. I think I see four NCOs with gold chevrons – three worn on the left sleeve and one high on the left breast, but in each case the source is low-quality footage so I can’t tell if there was a central device on them (perhaps not, by analogy with the infantry), let alone what it might have been.

Headgear. A beret, of slightly elusive shade — brown with a greenish tinge, the extent of which seems to have varied somewhat. In earlier appearances it’s relatively brown while at the coronation it often seems a more olive-drab colour – a couple appear almost a light khaki, also. Solid colour fatigue caps occasionally seen.

Equipment. Uzis, with both wooden and collapsible stocks.[11] A confusing picture re: belts. Some wear TAP 51 belts with a holster on the right and Uzi magazine pouch and bayonet on the left, others the same arrangement but with white parade belts with gold open buckles, others the same but the belts have gold closed buckles (device unclear), others have their tunics tucked into their trousers, showing a US-style solid buckle trouser belt, onto which the Uzi pouch is sometimes fixed, with the pistol belt over and atop it. Titley gives them “Kalashnikov assault rifles”.[12]

The Air Force.

Very little visual evidence is available.

Fig. 30. Aviateur de 1er Classe, Air Force, 1975.

Fig. 31. Air force beret badge.

Parade dress (“prise d’armes”). [Fig. 30] Seen by me only on enlisted men. Type A camouflage uniform and TAP belts. Navy blue beret. Beret badge as illustrated [Fig. 31]. Rank slides. I don’t have a front or left-hand view of this uniform so can’t comment on whether an aiguillette or pucelle was worn – possibly, and no, I would guess.

Fig. 32. Capitaine, Air Force, 1977.

Fig. 33. Air force cap badge.

Service dress (“tenue vareuse”) (officers). [Fig. 32] This seems to have been the same as for the infantry, except with a white cap crown. The chinstrap seems to have been of the “rectangular” form.

Service dress (“tenue vareuse”), insignia. I can’t get a good view of the cap badge and the illustration [Fig. 33] is my best reconstruction. The backing seems to have been somewhat oversized. Black(?) full detachable shoulder boards with rank stripes and some sort of device, entirely illegible. It doesn’t look like the spread eagle apparently in current CAR use. Shoulder title as per the infantry, at least on the left shoulder. Unclear if a shield was worn on the left shoulder. Also unclear if the collar badges were different to the infantry – they’re visible in one bit of footage but I can’t tell if they show a wreath or wings. The one man in this dress I can find with a right breast pocket visible isn’t wearing a pucelle.

Fig. 34. Commandant, Air Force, 1970

Khaki service dress. [Fig. 34] As per the infantry, worn with the peaked cap (double cords). Again, no pucelle seems to have been worn.

Equipment. MAS-49 rifles.

The Navy.

The modern CAR apparently maintains a small riverain force. Low-quality 1970 footage shows Bokassa and the Romanian ambassador reviewing a naval honour guard in Bangui. Uniform (to the very limited extent I can tell) seems to have been entirely French in style: officers with white jackets and caps, men in “square rigs”, dark band/light crown caps with pompon (the footage is black-and-white so colours are unclear). The enlisted men are armed with MAS-36 rifles.

The navy was evidently still in existence, to whatever extent, in 1977 — footage from that year, taken earlier than the coronation, offers an extremely low-quality view of officers and men from which no details can be recovered. The navy isn’t seen at the coronation and isn’t mentioned in Keegan, so had perhaps been disbanded by 1979.

The Gendarmerie.

As a general preliminary comment, the shades of blue present a degree of difficulty here, exacerbated if not outright caused by the low quality of much of the source material. The kepi was a lightish blue. A few, worn by by officers, appear a darker shade — these are seen both early and late, and officers wearing darker kepis seems to have become consistent practice by the middle 1980s. Certainly however the normal lightish shade is also seen worn by officers. The collar patches and shoulder boards were evidently darker: in some photos/footage they appear almost black, in others a lighter shade. The peaked cap, when introduced, was a midnight blue shade. I’ve elected to standardise all the gendarmerie insignia as midnight blue for the purposes of these illustrations, but I note here that it may have been lighter, at least some of the time.

Fig. 35. Gendarme, Gendarmerie, 1970.

Fig. 36. Officer, Gendarmerie, 1976.

Parade dress (“prise d’armes”). [Figs. 35-36] Khaki long-sleeved shirt, worn with sleeves down, pleated breast pockets, buttons unobtrusive khaki-ish colour, tucked into khaki trousers with rear but seemingly no cargo pockets. Shirt worn closed at the neck with a tie – colour unclear, either black or very dark blue or green. Silver tie clip as per the infantry. In 1970 footage a white cross-strap is worn [Fig. 35], but this has disappeared by 1975 [Fig. 36]. White belts with either a two-pronged open buckle or a solid buckle with bursting grenade badge, both seemingly gold instead of silver. The two seem to have been worn interchangeably by 1975 – I assume the open-buckle belt was originally intended to take the cross-strap. Black shoes. In 1970 footage white gaiters of WWII British style are worn, but by 1975 these have become white “spat” type gaiters of French style, at least for the colour party. Worn with the kepi and later the peaked cap (see the introduction for my thoughts on the changeover date). The earlier type uniform included white gloves — the later one didn’t, but the colour party still wore white gloves with gauntlets.

Fig. 37. Gendarmerie cap/beret badge.

Fig. 39. Gendarmerie sleeve shield.

Fig. 40. Gendarmerie pucelle.

Fig. 41. Gendarmerie shoulder board.

Fig. 41A. Gendarmerie shoulder board (variant).

Parade dress (“prise d’armes”), insignia. For all ranks, white shoulder trefoils on dark (black or blue) backing, silver buttons. These seem not to have borne rank insignia, so the only indication of officers’ rank would have been the amount of bands on the kepi while the kepi was worn, and for the men nothing at all(?) An aiguilette worn from the left shoulder, white in the “peaked cap period” and a different, darker colour (blue, presumably?) in the “kepi period”. This looped around a button on the front flap of the shirt, covered by the necktie, so the “points” of the aiguilette, which hung straight down, were invisible unless the tie was tied short or had shifted position. Gendarmerie shoulder patch as illustrated [Fig. 39] — I had taken the grenade, based on many clearish views of it in footage, to be gold, but a single surviving example has it in silver, so I follow that. A good view of the pucelle eludes me, but it was evidently of “shield and knight’s helmet” design — the illustration is my best guess [Fig. 40].

Fig. 42. Lieutenant, Gendarmerie, 1975.

Fig. 43. Capitaine, Gendarmerie, 1975.

Fig. 44. Commandant, Gendarmerie, 1977.

A different parade dress (“prise d’armes”). [Figs. 42-44] This is perhaps better conceptualised as a sort of “on duty, but at a formal occasion” uniform. Lizard camouflage (Types A, B and D attested) and greenish TAP 51 belts, other times white belts. The matching headgear seems to have been the kepi, and later the beret (perhaps at the time the kepi was replaced with the peaked cap for other orders of dress). Officers wore full detachable shoulder boards. I think all the ones I’ve seen in footage bore only a grenade device [Fig. 41], but the single actual surviving specimen I have seen has two chevrons above the grenade [Fig 41A]. Alternatively, slides off the sleeve tabs with the type D uniform [Fig. 44]. It appears from little evidence that enlisted men wore full shoulder boards also. A pucelle worn, at least by officers, but not consistently. Gendarmerie officers escorting Bokassa’s vehicle at the coronation wore camouflage (Type D) with beret [Fig. 44]. These officers wore medals and TAP 51 belts with leather pistol holsters. One wears a white aiguillette on the left shoulder, the other, curiously, doesn’t. In a black-and-white 1975 photo one officer can be seen wearing a “Gueneau” helmet with bright metal grenade badge [Fig. 42]. I can see no helmets elsewhere.

Fig. 45. Capitaine, Gendarmerie, 1972.

Fig. 46. Capitaine, Gendarmerie, 1969.

Fig. 46A. Gendarmerie collar patch.

Service dress (“tenue vareuse”) (officers). [Fig. 45] As per the infantry except where noted. Worn with the kepi – presumably the peaked cap later replaced it though I have no evidence either way. Collar patches as illustrated [Fig. 46A]. Pucelle worn. Darkish blue detachable shoulder boards.

Service dress (“tenue vareuse”) (officers, “winter” version). [Fig. 46] As for the infantry. Worn with the kepi.

Fig. 47. Sous-Lieutenant, Gendarmerie, 1970.

Fig. 47A. Gendarme, Gendarmerie, 1977.

Fig. 47B. Gendarme, Gendarmerie, 1975.

Khaki service dress. [Fig. 47] The same as parade dress, minus the white elements and the aiguilette. Darkish blue detachable shoulder boards or rank slides worn instead of the trefoils. A narrow US-style trouser belt with solid buckle was used. I haven’t seen this worn by enlisted men, or in the peaked cap era by officers or enlisted men.

Fatigue dress. [Fig. 47A] Four-pocket jacket of infantry style, with pucelle. Worn with beret. No doubt generic army-style shirts, etc, or the khaki service dress shirt with open collar, could be found.

Gendarmerie motorcycle squadron. [Fig. 47B] First seen (by me) in 1968, and last at Giscard d’Estaing’s visit to Bangui in 1975. It may have subsequently been disbanded for the benefit of the two police motorcycle units. Dark blue four-pocket tunic with white shirt, black tie, silver tie clip. White shoulder trefoils and white aiguillette on the left shoulder — the latter is worn haphazardly and it’s rather difficult to ascertain what the intended arrangement was supposed to have been. Standard gendarmerie collar patches and sleeve shield. Rank chevrons (and presumably also rank stripes for officers) on the lower sleeves. Dark blue trousers, black footwear of unclear nature (boots vs. shoes). White crash helmet with no insignia, worn with goggles. Pucelle worn. Some other accoutrements of unclear nature. There seems to have been a whistle, worn on a white lanyard running around the neck and into the left breast pocket, plus perhaps another white cord — I’ve left this off the illustration as I don’t know what it might have been. Also, some sort of blue circular insignia worn on the belt cross-strap. I’ve given this a green box as it was clearly part of the uniform, but I cannot begin to identify it.

Kepi. Rigid, medium blue (sometimes (later?) dark blue for officers) body with medium green top. Silver chinstraps and top bands. Silver grenade badge. Officers had silver lace bands around the top of the crown, in increasing number based on seniority (I assume in detail this followed the French manner). The top sometimes had quatrefoil embroidery in the French style, and was probably always intended to, but photos show this missing on some specimens.

Peaked cap. This and the beret seem to have replaced the kepi. After Bokassa’s downfall the kepi reappeared. Dark blue crown, dark green band piped white or silver (unclear – I assume silver by analogy to the kepi) at top and bottom, white chinstrap, black peak. Badge as illustrated, embroidered [Fig. 37].

Beret. Navy blue (visibly somewhere between the light kepi shade and the dark insignia shade) with the same badge as on the peaked cap [Fig. 37]. This likewise seems to have been re-replaced with the kepi in the post-Bokassa era.

Equipment. White pistol holsters seen with the white belts. Berthier carbines, which were used with white slings for parades but were probably also the general armament. No pouches appear to have been carried on parade. MAT-49s.

The Mobile Gendarmerie.

The gendarmerie used silver distinctions, which is in keeping with French practice. Men can be seen wearing (more or less) standard gendarmerie uniforms, but with gold grenades and lace. In France, as I understand it, there is a “mobile gendarmerie”, distinct from the regular gendarmerie, which employs the same distinctions as the regular gendarmerie but with gold in place of silver. So I think this is what we’re seeing here.

These men are first seen in early 1975 where they dress as gendarmerie, but with gold distinctions as noted. The blue elements (kepi, shoulder boards) seem to be a consistently darkish shade — not midnight blue but a solid dark blue. By 1977, with the caveat I take this from very low-quality footage, they seem to have become black, and in 1979 a man appears in footage with black shoulder straps and a black beret.

I assume these men were supposed to dress the same as the regular gendarmerie save for the gold/silver distinction. Only the orders of dress I have actually seen are given below. In 1975 the pucelle seems to have just been the normal gendarmerie one, in silver — what it may have done afterwards (if anything) I do not know.

Khaki service dress (officers). As per gendarmerie khaki service dress except with gold distinctions. Black detachable shoulder boards and black kepi with (so far as I can see) green top. The shirt was worn open at the neck – unclear if this was regulation or just what I happen to see in the footage.

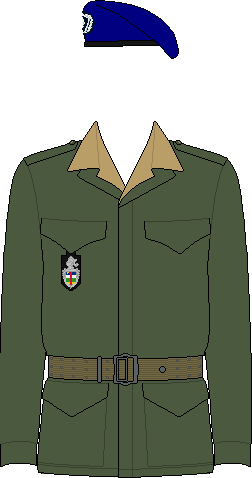

Fig. 48. Sergent, Mobile Gendarmerie, 1975.

Fig. 48A. Brigadier(?), Mobile Gendarmerie, 1979.

Fig. 48B. Mobile gendarmerie beret badge.

Fig. 48C. Mobile gendarmerie shoulder board.

Khaki service dress (enlisted men). [Figs. 48 and 48A] As per gendarmerie khaki service dress except with gold distinctions. Dark blue, later black, detachable shoulder boards [Fig. 48C]. A dark blue kepi with gold distinctions, later a black beret with curious large bursting grenade badge [Fig. 48B]. It seems to have borne some kind of central device which is illegible and so I’ve left it off the illustration. Shirt worn open at the neck.

Fig. 49. Lieutenant, Mobile Gendarmerie, 1977.

Camouflage parade/service (etc.) dress. [Fig. 49] An officer in this dress may be visible – if so, the same as the regular gendarmerie, but with gold/black distinctions as above, type A lizard.

Officers are seen wearing kepis in 1977 circa the coronation – that is, over a year after other branches (including the regular gendarmerie) seem to have exchanged theirs for peaked caps. The black beret is attested once, in footage from seemingly right after Bokassa’s overthrow. The regular gendarmerie seem to have taken up berets at the same time as the peaked caps. Does the presence of a beret in circa September 1979 mean that a peaked cap/beret combination was introduced for the mobile gendarmerie sometime after the coronation? I do not know. The beret badge is really very curious – it’s a grenade, but not one of gendarmerie style – its closest resemblance is to the badge worn on the front of the French infantry helmet in the world wars.

Generals.

As with any army the generals seem to have suited themselves in manners of dress, to some extent, and any or all of the items described here could have been non-regulation based on the whims of the wearer. Bokassa’s own uniforms were wholly idiosyncratic and I deal with them elsewhere.

Fig. 50. Army Général de Brigade, 1975.

Fig. 51. Army Général de Brigade, 1978.

Fig. 52. Generals’ collar patch.

Infantry generals’ service dress (“tenue vareuse”). [Figs. 50-51] As per infantry except as noted. The peaked cap had gold foliate embroidery around the band. Instead of shoulder straps, khaki passants with gold foliate embroidery. When an aiguilette was worn it was fixed under the passant and attached to a button under the lapel. Unclear if the sleeve title was worn – no, I think. Stars were worn above the cuff in the French manner. There seems to have been two variants beyond this. We see some generals wearing the standard infantry cap badge and collar patches, and the “Quartier Général” pucelle. The arm shield is unclear. Other generals had different collar patches: black pentagonal with an elaborate wreathed “all arms” design [Fig. 52]. This uniform was accompanied by a different arm shield, though the design is illegible. I assume the cap badge was the “all arms” design as on the collar patches but I can’t confirm. The pucelle is unseen but surely must have been the “Quartier Général”. The “infantry badge” type uniform seems to post-date the other type, but I don’t want to presume that one replaced the other without more evidence.

Fig. 53. Army Général de Brigade, 1978.

Infantry generals’ service dress (“tenue vareuse”) (“winter” version). [Fig. 53] As above but in the darker “Terre de France” material, as described in the infantry section. Worn with red beret with stars above the badge. The one general seen in this uniform wears infantry collar patches and beret badge.

Fig. 54. Army Général de Brigade, 1977.

Infantry generals’ field/service uniform. [Fig. 54] Red beret with infantry badge, with stars above. Black shoulder slides with stars. Green fatigues with TAP 51 belt illustrated, but presumably any and every possible item of dress was worn at some point. Worn with full medals.

Fig. 55. Gendarmerie, Général de Brigade, 1975.

Fig. 56. Gendarmerie, Général de Brigade, 1977.

Gendarmerie generals’ service dress (“tenue vareuse”). [Figs. 55-56] As per infantry generals except as noted. Curious slit pockets on the lower tunic, on the single individual I’ve seen where they’re visible. A kepi (seemingly in khaki – I lack a colour photo) with stars on the front, later a peaked cap with foliate band and a badge of seemingly similar design to the gendarmerie beret badge, but with a bar(?) behind the grenade. The standard gendarmerie arm shield and pucelle. The lack of colour throws up several uncertainties – I assume the “metal” was all silver instead of gold and the black parts were blue.

École Militaire des Enfants de Troupe Jean-Bédel Bokassa.

A military school of some sort, as the name suggests.

Parade uniform. Type A or D uniform with midnight blue beret. In earlier footage there is a beret which shows up as white — I would guess a very light tan. Gold circular beret badge and gold shield pucelle – further details are illegible in both cases. A “first day cover” commemorating the school shows a shield with stylised bursting grenade, sword and outline of the country – I don’t think this is what I see in either case in the photographs. White gloves and TAP 51 belts.

References:

Copyright date 1979. The section on the CAE was written while Bokassa was still in power, likewise a short appendix added as the book was going to press.

Keegan, 121.

In footage of a parade held on 1 December 1975.

Though exceptions do exist. For a French example, the vestigial re-established Vichy army of 1943 had a single regiment, titled the “1st Regiment of France”.

Jean-Marc Marill, Dictionnaire des Opérations Extérieures de l'Armée Française de 1963 à nos Jours (2018), 60.

Brian Titley, Dark Age: The Political Odyssey of Emperor Bokassa (1997), 99.

The one figure I base this off seems to be a lance-corporal (i.e., with red chevrons only) but nevertheless his sword is gold.

Titley, 24.

Also, undated footage shows a man in Guard uniform (or what I take to be so) directing traffic in Bangui(!!)

One man in a 1975 photo may be a Guard officer in “vareuse” (he is otherwise unaccountable) but the view is nowhere near clear enough to comment further. See Fig. 78 in part 2.

We read that the Guard were trained by an exiled Israeli general, which may explain the presence of this weapon (Titley, 99).

Titley, 109.

5 March 2022

Last revisions: 26 September 2022